Changing learning into something better

January 1, 2015

Many of the most inspiring documents are strongly tied with a date. The U.S. Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776; Charter 77 came out in January 1977; Dogme 95 was made in 1995. Ideas take time to change and grow. This manifesto shows our ideas, what we think the future should be, and what we have learned about learning and education. This text helps us understand how we have done so far, and what actions we need to take next.

In a world obsessed with the unknown and a growing sense that our schools are not useful, how can we make sure we as individuals, our communities, and the planet are successful? We need to change education into something better.

What we have learned so far

The future is already here - it’s not available to everyone (rephrased from William Gibson in Gladstone, 1999). The field of education is behind most industries because our ideas often look backward, not forward. We teach about books that were already written, but not the future of writing. We teach important ideas in math, but not how to create new math ideas needed for the future. Everything “new” in learning has already happened in different ways, in bits and pieces, at different places. The full impacts for ourselves and our organizations will only happen when we are brave enough to learn from each others’ experiences. In everything we do, we need to keep the future in mind.

Old schools can’t teach new kids. We need to remake and build a clear understanding of what we are teaching for, why we do it, and for whom our schools serve. The main required schooling is based on an old, 18th century model for creating factory workers and government workers. Since we do not have a lot of factories anymore, why are schools still trying to make factory workers? We need to support students to be creative, come up with new ideas, and use their abilities to figure out new ways to improve the world. We can’t use old thinking to solve new problems. We are all helping to create futures with good outcomes that include all people in the world.

Kids are people, too. Every student deserves the respect and the responsibilities like an adult. Kids need an active say in what they do. Students should be able to chose what to learn, what time to learn, and how to do it, instead of teachers telling them. This is the way to include all kinds of kids in learning. It’s important not to leave anyone out because everyone should get to learn. Students should be able to do what they want to do in their own ways that are best for them as long as it doesn't bother other kids’ learning (adapted from EUDEC, 2005)

Jumping off a cliff is exciting when you make the choice to do it yourself, but not when someone else makes the choice for you. In other words, when teachers tell students what they have to learn, it does not maximize their learning. It takes away students’ curiosity and destroys their interest in learning things for fun. We need to teach and allow students to learn in all different kinds of ways, including kids teaching and learning from each other. Teachers must create space to allow students to choose if, and when, to make the choice for themselves. Failing is a natural part of learning where we can always try again. In a flat learning environment, the teacher’s role is to help make sure the learner makes a good decision. Failing is okay, but creating failures is not.

We should measure what we know is important, not make something important just because we test it. Kids are being tested more and more, and this is spreading throughout the world's schools! In the world, all of the states and countries are trying to prove they are the best even though none of them are. What is really bad is that schools are making government workers and people who make laws that do not know how to understand test scores. New and creative ideas go away when we worry about measurement. We need to stop required testing and take that money and use it for real and meaningful things for kids.

-

If “technology” is the answer, what was the question? We seem to have a love for new technologies, even though we don’t know what there are for or how they impact learning. Technologies are great for doing what we have been doing in the past better, but using new technologies to do the same old stuff in the classroom is a lost cause. Black boards have been replaced by whiteboards and SMART Boards. Books have been replaced by iPads. It’s too much technology! But, nothing has changed, and we still spend a lot of time and money on these tools, and waste our chances to show how they might change what we learn and how we do it. By doing what we have always done with technologies, schools focus more on managing the tools than growing students’ minds and their meaningful use of the tools.

If digital skills are invisible, then learning with technology in schools should be, too. Most of the learning we do is through real life experiences, not from a teacher telling us what to learn. We call this invisible learning (Cobo & Moravec, 2011). Technologies are everywhere and they help us learn invisibly. If we schools want kids to come out of school being creative people, then we have to use technologies to support their ideas. Schools should have computers, but not for work, they should be used for creative/design projects. Do not make technology the focus of learning, but keep the technology there so that students can use it create their own learning and figure out their own new ways for using the tools.

We cannot manage knowledge. Sometimes the concepts of knowledge and innovation are mixed up or confused with the concepts of data and information instead. We trick ourselves into thinking that we give kids knowledge when we are just testing them for what information they can repeat. Data are all the parts that make up information. Knowledge is about taking information and creating your own meaning. We innovate when we take action with what we know, to create new value. Understanding this difference shows a huge problem for schools and teaching: We are good at managing information, but when we try to manage students’ knowledge it turns back to just information.

“The network is the learning” (Siemens, 2007). The new ways of teaching and learning of this century are not carefully planned, instead they are created as we go along. We learn when we connect with each other, and as we connect with each other, so does our learning. In this way learning, when we meet together we learn from each other, and from that we can create new knowledge. We share our experiences, and create new (group) knowledge as a result. We should focus on the abilities of each person and help them learn to make connections on their own and figure out how their special knowledge and skills can be used to solve new problems.

The future belongs to nerds, geeks, makers, dreamers, and knowmads. Not everybody will or should become a business owner, but everyone should develop the skills of business owners. The people who do not will be at a disadvantage. Our schools should focus on the developing “entreprenerds,” people who use their knowledge to dream, create, make, explore, learn and create business, cultural, or social experiences. Kids should be taught to take risks and enjoy the learning as much as the final outcome, without fearing the possible failures or mistakes that might happen along the way.

Break the rules, just figure out why first. Our schools are based on following the rules, making kids follow the rules, and not wanting to make things better. The creative ideas of students, staff, and our schools are killed by the system. It is easier to be told what to think than to think ourselves. To fix this, we need to ask questions and build knowledge and understand what we have created and what we would like to do about it. Then, we can create breaks from the system that are different from what we have now that might create real change.

We must and can build trust within our schools and communities. As long as our schools are based on fear, stress, and distrust, there will always be challenges. In a project called Minnevate! (MASA, 2014), the researchers found that if we want teachers to put all of their knowledge and skill together to change education, we need communities that we can work with and we also need to work with our communities. This means we need to find new ways for everyone, including students, schools, governments, businesses, parents, and communities to work together, centered on trust, to create new education futures together.

Some say these ideas require a revolution if we want it to happen. Others say we need to be innovative. We believe we need both, or as Ronald van den Hoff (2013) says: “What what we really need is an innovution!” (p. 236). And, this is what we need to do: To innovute with not only our ideas, but also the ideas of what we have learned through our individual efforts, and together, globally.

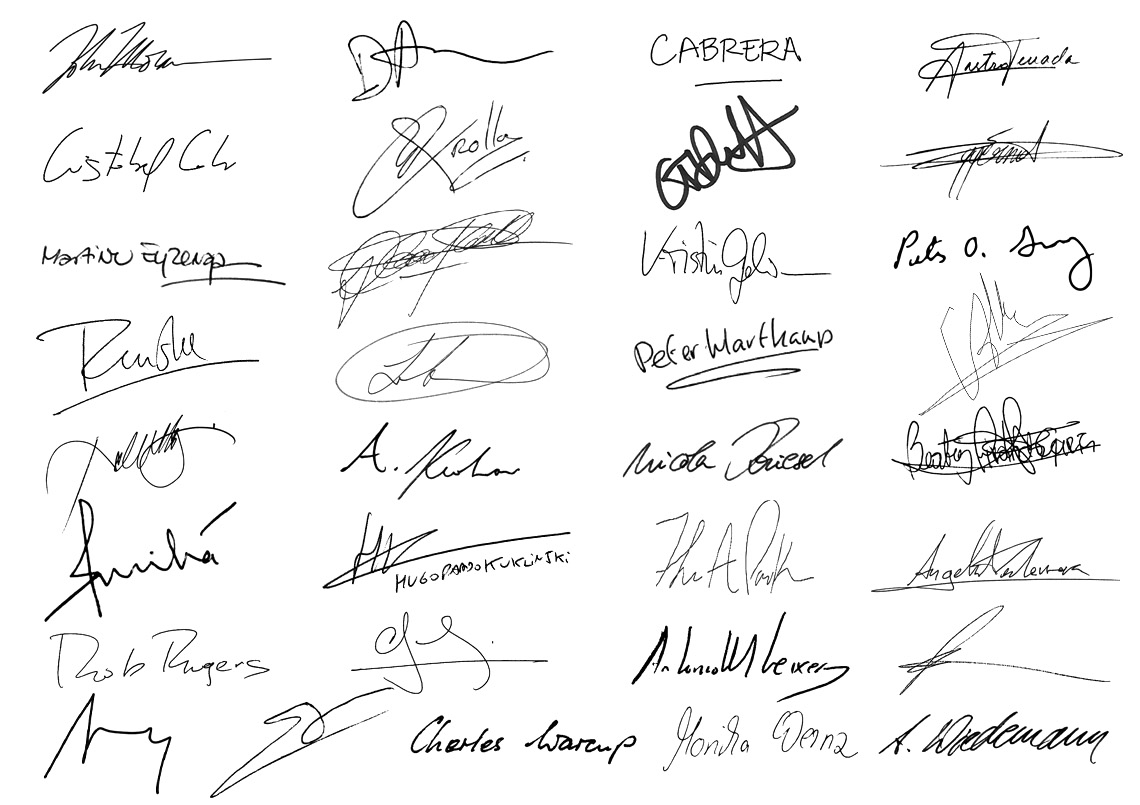

Initial signatories

We are: John Moravec, PhD, Education Futures (principal author, USA); Daniel Araya, PhD, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (USA); Daniel Cabrera, MD, Mayo Clinic (USA); Alexandra Castro, Westhill Institute (Mexico); Cristóbal Cobo, PhD, Fundación Ceibal (Uruguay); Guido Crolla, HAN University of Applied Sciences (Netherlands); Chloe Duff, European Democratic Education Community (UK); Maaike Eggermont, Sudbury School Ghent (Belgium); Martine Eyzenga, Diezijnvaardig (Netherlands); José García Contto, Universidad de Lima (Peru); Kristin Gehrmann, Demokratische Schule München (Germany); Peter Gray, PhD, Boston College (USA); Renske de Groot, arts educator (Netherlands); Leif Gustavson, PhD, Pacific University (USA); Peter Hartkamp, The Quantum Company (Netherlands); Christel Hartkamp-Bakker, PhD, Newschool.nu (Netherlands); Pekka Ihanainen, Haaga-Helia School of Vocational Teacher Education (Finland); Aaron Keohane, Summerhill School (UK); Nicola Kriesel, BFAS e.V. (Germany); Beatriz Miranda, Aprendamos (Ecuador); Sugata Mitra, PhD, Newcastle University (UK); Hugo Pardo Kuklinski, PhD, Outliers School (Spain); Tomis Parker, Agile Learning Centers (USA); Angela Peñaherrera, Fraschini&Heller (Ecuador); Robert Rogers, MD, University of Maryland (USA); Carlos Scolari, PhD, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Spain); António Teixeira, PhD, Universidade Aberta (Portugal); Stephanie Thompson, Beach Haven Primary (New Zealand); Max Ugaz, Economía Digital SAC (Peru); Evert-Jan Ulrich, Dutch Innovation School (Netherlands); Charles Warcup, Sudbury-Schule Ammersee (Germany); Monika Wernz, Sudbury-Schule Ammersee (Germany); Alex Wiedermann, Sudbury-Schule Ammersee (Germany)

Share and sign the manifesto!

The easiest way to show your support for this manifesto is to share it with your friends and colleagues. On Twitter, please use the hashtag #manifesto15.

Add your signature and thoughts here

Thank you!

Gratitude goes to everybody who contributed their input to help make this document great, especially the initial signatories who provided early feedback and support for the final document.

This version of the original English document was translated for kids by Hillel Killorn, a 6th grade student.

Contact the authors

Email us at manifesto15@educationfutures.com.

References and recommended readings

Cobo, C., & Moravec, J. W. (2011). Aprendizaje Invisible: Hacia una nueva ecología de la educación. Barcelona: Laboratori de Mitjans Interactius / Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona. http://www.aprendizajeinvisible.com

EUDEC. (2005). EUDEC guidance document. European Democratic Education Community. Retrieved January 1, 2015 from http://www.eudec.org/Guidance+Document#Article_1:20_Definitions

Gladstone, B. (Producer). (1999, November 30). The science in science fiction [Radio broadcast episode]. In Talk of the Nation. Washington, DC: National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1067220

Gray, P. (2013). Free to learn. New York: Basic Books.

van den Hoff, R. (2013). Society30: Knowmads and new value creation. In J. W. Moravec (Ed.), Knowmad Society (pp. 231–252). Minneapolis: Education Futures. http://www.knowmadsociety.com

MASA. (2014). Minnevate! 2013-2014 activity report. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Association of School Administrators. http://minnevate.mnasa.org

Moravec, J. W. (Ed.) (2013). Knowmad Society. Minneapolis: Education Futures. http://www.knowmadsociety.com

Siemens, G. (2007). The network is the learning. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rpbkdeyFxZw

Manifesto 15 by John Moravec et al is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.